From the Manual Of

Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Mango

History And

Distribution

Alphonse DeCandolle considered it probable that the mango could be

included among the fruits which have been cultivated by man for 4000

years. Its prominence in Hindu mythology and religious observance

leaves no doubt as to its antiquity, while its economic importance in

ancient times is suggested by one of the Sanskrit names, am, which has

an alternative meaning of provisions or victuals.

Dymock,

Warden, and Hooper (Pharmacographia

Indica) give the following resume

of its position in the intellectual life of the Hindus:

"The

mango, in Sanskrit Amra, Chuta and Sahakara, is said to be a

transformation of Prajapati (lord of creatures), an epithet in the Veda

originally applied to Savitri, Soma, Tvashtri, Hirangagarbha, Indra,

and Agni, but afterwards the name of a separate god presiding over

procreation. (Manu. xii, 121.) In more recent hymns and Brahmanas

Prajapati is identified with the universe.

"The tree provides

one of the pancha-pallava or aggregate of five sprigs used in Hindu

ceremonial, and its flowers are used in Shiva worship on the

Shivaratri. It is also a favorite of the Indian poets. The flower is

invoked in the sixth act of Sakuntala as one of the five arrows of

Kamadeva. In the travels of the Buddhist pilgrims Fah-hien and Sung-yun

(translated by Beal) a mango grove (Amravana) is mentioned which was

presented by Amradarika to Buddha in order that he might use it as a

place of repose. This Amradarika, a kind of Buddhic Magdalen, was the

daughter of the mango tree. In the Indian story of Surya Bai (see Cox,

Myth. of the Arian Nations) the daughter of the sun is represented as

persecuted by a sorceress, to escape from whom she became a golden

Lotus. The king fell in love with the flower, which was then burnt by

the sorceress. From its ashes grew a mango tree, and the king fell in

love first with its flower, and then with its fruit; when ripe the

fruit fell to the ground, and from it emerged the daughter of the sun

(Surya Bai), who was recognized by the prince as his long lost wife."

When

introduced into regions where climatic conditions are favorable, the

mango rapidly becomes naturalized and takes on the appearance of a wild

plant. This fact, together with the long period of time during which it

has been cultivated throughout India, makes it difficult to determine

the original home of the species.

Sir Joseph Hooker (Flora of

British India) considered the mango to be indigenous in the tropical

Himalayan region, from Kumaon to the Bhutan hills and the valleys of

Behar, the Khasia mountains, Burma, Oudh, and the Western peninsula

from Kandeish southwards. He adds, "It is difficult to say whether so

common a tree is wild or not in a given locality, but there seems to be

little doubt that it is indigenous in the localities enumerated."

Dietrich Brandis (Indian Trees) says it is indigenous in Burma, the

Western Ghats, in the Khasia hills, Sikkim, and in the ravines of the

Satpuras. R. S. Hole, of the Imperial Forest Research Institute at

Dehra Dun, considers that the so-called wild mangos which are found in

many parts of India are mostly forms escaped from cultivation, as shown

by the fact that they are always near streams or foot-paths in the

jungle, where seeds have been thrown by passing natives.

Alphonse

DeCandolle says: "It is impossible to doubt that it is a native of the

south of Asia and of the Malay Archipelago, when we see the multitude

of varieties cultivated in those countries, the number of ancient

names, in particular a Sanskrit name, its abundance in the gardens of

Bengal, of the Dekkan peninsula, and of Ceylon, even in Rheede's time.

. . . The true mango is indicated by modern authors as wild in the

forests of Ceylon, the regions at the base of the Himalayas, especially

towards the east, in Arracan, Pegu, and the Andaman Isles. Miquel does

not mention it as wild in any of the islands of the Malay Archipelago.

In spite of its growing in Ceylon, and the indications, less positive

certainly, of Sir Joseph Hooker in the Flora of British India, the

species is probably rare or only naturalized in the Indian peninsula."

Most species of Mangifera

are natives of the Malayan region. Sumatra in particular is the home of

several. While it is known that the mango has been cultivated in

western India since a remote day, and we find it to-day naturalized in

many places, it seems probable that its native home is to be sought in

eastern India, Assam, Burma, or possibly farther in the Malayan region.

The

Chinese traveler Hwen T'sang, who visited Hindustan between 632 and 645

a.d., was the first person, so far as known, to bring the mango to the

notice of the outside world. He speaks of it as an-mo-lo, which Yule

and Burnell consider a phonetization of the Sanskrit name amra. Several

centuries later, in 1328, Friar Jordanus, who had visited the Konkan

and learned to appreciate the progenitors of the Goa and Bombay mangos,

wrote, "There is another tree which bears a fruit the size of a large

plum, which they call aniba." He found it "sweet and pleasant." The

common name which he used is a variation of the north Indian am or

amba. Six years later (1334) Ibn Batuta wrote that "the mango tree

('anba) resembles an orange tree, but is larger and more leafy; no

other tree gives so much shade." John de Marignolli, in 1349, says,

"They also have another tree called amburan, having a fruit of

excellent fragrance and flavor, somewhat like a peach." Var-thema, in

1510, mentioned the mango briefly, using the name amba. Sultan Baber,

who wrote in 1526, is the first to distinguish between choice and

inferior varieties. He says, "Of the vegetable productions peculiar to

Hindustan one is the mango, (ambeh). . . . Such mangos as are good are

excellent."

The island of Ormuz, in the mouth of the Persian

Gulf, was settled in early days by the Portuguese and became one of the

great emporiums of the East. Garcia de Orta, a Portuguese from Goa,

wrote in 1563 that the mangos of Ormuz were the finest in the Orient,

surpassing those of India. It is probable, however, that the mangos

known at Ormuz were not grown on the island itself, since it has very

little arable land and water is exceedingly scarce. The Cronica dos

Reys Dormuz (1569) says that mangos were brought to Ormuz from Arabia

and Persia. Later, in 1622, P. della Valle speaks of the mangos grown

on the Persian mainland at Minao, only a few miles from Ormuz.

The

Ain-i-Akbari, an encyclopedic work written during the reign of Akbar

(about 1590), contains a lengthy account of the mango. Akbar, it may be

remembered, was the Mughal emperor who planted the Lakh Bagh at

Darbhanga, and in other ways stimulated the cultivation of fruit-trees

throughout northern India. Abu-1 Fazl-i-'Allami, author of the Ain

(translated by Blochmann), writes:

"The Persians call this fruit

Naghzak, as appears from a verse of Khusrau. This fruit is unrivalled

in color, smell, and taste; and some of the gourmands of Turan and Iran

place it above muskmelons and grapes. In shape it resembles an apricot,

or a quince, or a pear, or a melon, and weighs even one ser and

upwards. There are green, yellow, red, variegated, sweet and subacid

mangos. The tree looks well, especially when young; it is larger than a

nut tree, and its leaves resemble those of a willow, but are larger.

The new leaves appear soon after the fall of the old ones in the

autumn, and look green and yellow, orange, peach-colored, and bright

red. The flower, which opens in the spring, resembles that of the vine,

has a good smell, and looks very curious. . . . The fruit is generally

taken down when unripe, and kept in a particular manner. Mangos ripened

in this manner are much finer. They commence mostly to ripen during

summer and are fit to be eaten during the rains; others commence in the

rainy season and are ripe in the beginning of winter; the latter are

called Bhadiyyah. Some trees bloom and yield fruit the whole year; but

this is rare. Others commence to ripen, although they look unripe; they

must be quickly taken down, else the sweetness would produce worms.

Mangos are to be found everywhere in India, especially in Bengal,

Gujrat, Malwah, Khandesh, and the Dekhan. They are rarer in the Panjab,

where their cultivation has, however, increased since his Majesty made

Lahor his capital. A young tree will bear fruit after four years. They

also put milk and treacle around the tree, which makes the fruits

sweeter. Some trees yield in one year a rich harvest, and less in the

next; others yield for one year no fruit at all. . . ."

The name

mango, by which this fruit is known to English-speaking as well as

Spanish-speaking peoples, is derived from the Portuguese manga.

According to Yule and Burnell, the Tamil name man-kay or man-gay is the

original of the word, the Portuguese having formed manga from this when

they settled in western India. Skeat traces the origin of the name to

the Malayan manga, but other writers consider the latter to have been

introduced into the Malay Archipelago from India. The name mango is

used in German and Italian, while the Dutch have adopted manga or

mangga, and the French form is mangue.

In the Malay Archipelago

and in many parts of Polynesia mangos are plentiful. W. E. Safford l

writes, "The mango tree is not well established in Guam. There are few

trees on the Island, but these produce fruit of the finest quality.

Guam mangos are large, sweet, fleshy, juicy, and almost entirely free

from the fiber and flavor which so often characterize the fruit."

Excellent mangos were formerly shipped from the French island of Tahiti

to San Francisco. Many choice varieties have been planted in the

Hawaiian Islands. J. E. Higgins has written a bulletin on mango culture

in this region.

On the tropical coast of Africa, extending south

to the Cape of Good Hope, and in Madagascar, mangos are common. The

French island of Reunion is the original home of several varieties now

cultivated in the West Indies and Florida.

In Queensland,

Australia, attention has been given to the asexual propagation of this

fruit, and a limited number of choice Indian varieties have been

introduced.

In the Mediterranean region the species is not

entirely successful. Trees are reported to have produced fruit in

several localities, but nowhere have they become commonly grown. In

Madeira and the Canary Islands they are more at home; Captain Cook,

when on his first voyage of discovery, reported in 1768 that mangos

grew almost spontaneously in Madeira. C. H. Gable, who has recently

worked on the island, says there are now only a few trees to be found,

but that these bear profusely.

The Portuguese are given the

credit for bringing the mango to America. It is believed to have been

first planted at Bahia, Brazil, at an uncertain date probably not

earlier than 1700. Captain Cook found in 1768 that the fruit was

produced in great abundance at Rio de Janeiro. In the West Indies it

was first introduced at Barbados in 1742 or thereabouts, the "tree or

its seed" having been brought from Rio de Janeiro. It did not reach

Jamaica until 1782. Its introduction into the latter island is

described by Bryan Edwards:1 "This plant, with

several

others, as well as different kinds of Seeds, were found on board a

French ship (bound from the Isle de France for Hispaniola) taken by

Captain Marshall of his Majesty's Ship Flora, one of Lord Rodney's

Squadron, in June, 1782, and sent as a Prize to this island. By Captain

Marshall, with Lord Rodney's approbation, the whole collection was

deposited in Mr. East's garden, where they have been cultivated with

great assiduity and success." Thirty-two years after its introduction,

John Lunan stated that the mango had become one of the commonest

fruit-trees of Jamaica.

1 Useful Plants of Guam.

It

is said to have been introduced into Mexico at the same time as the

coffee plant, early in the nineteenth century, the introducer having

been D. Juan Antonio Gomez of Cordoba. It is evident that Mexico has

received mangos from two sources; some from the West Indies, and others

from the Philippines, brought by the Spanish galleons which traded in

early times between Acapulco and Manila.

The cultivation of the

mango under glass in Europe was attempted at an early day. A writer in

Curtis' Botanical Magazine in 1850 says : "The mango is recorded to

have been grown in the hothouses of this country at least 160 years

ago, but it is only within the last twenty years that it has come into

notice as a fruit capable of being brought to perfection in England.

The first and, we believe, the most successful attempt was made by the

late Earl of Powis, in his garden at Walcot, where he had a lofty

hothouse 400 feet long and between 30 and 40 feet wide constructed for

the cultivation of the mango and other rare and tropical fruits; but

within these last few years we have known it to bear fruit in other

gardens."

In the United States, cultivation of the mango is

limited to southern Florida and southern California. It is believed the

species was first introduced into the former state by Henry Perrine,

who sent plants from Mexico to his grant of land below Miami in 1833.

These trees, however, perished from neglect after Perrine's death, and

many years passed before another introduction was made. According to P.

J. Wester, the second and successful introduction was in 1861 or 1862,

by Fletcher of Miami. The trees introduced in these early years were

seedlings. In 1885 Rev. D. G. Watt of Pinellas made an attempt to

introduce the choice grafted varieties of India. According to P. N.

Reasoner,1 Watt obtained from Calcutta eight

plants of the

two best sorts, Bombay and Malda. "They were nearly three months on the

passage, and when the case was opened five were dead; another died soon

after, and the two remaining plants were starting nicely, when the

freeze destroyed them entirely."

In 1888 Herbert Beck of St. Petersburg

obtained a shipment of thirty-five inarched trees from Calcutta. This

shipment included the following varieties: "Bombay No. 23, Bombay No.

24, Chuckchokia, Arbuthnot, Gopalbhog, Singapore, and Alphonse." In the

latter part of 1889 Beck reported to the Department of Agriculture that

all but seven of the trees had died. Further details regarding this

importation are lacking, but it is not believed that any of the trees

lived to produce fruit. On November 1, 1889, the Division of Pomology

at Washington received through Consul B. F. Farnham of Bombay, India, a

shipment of six varieties, as follows: "Alphonse, Banchore, Banchore of

Dhiren, Devarubria, Mulgoba, and Pirie." The trees were obtained from

G. Marshall Woodrow, at Poona. After their arrival in this country they

were forwarded to horticulturists on Lake Worth, Florida. Most of the

trees succumbed to successive freezes, but in 1898 Elbridge Gale

reported that one Alphonse sent to Brelsford Brothers was still alive,

but was not doing well; and that of the five trees sent to himself only

one, a Mulgoba, had survived. This tree began to bear in 1898, and is

still productive, although it has not borne large crops in recent

years. The superior quality of its fruit furnished the needed stimulus

to the development of mango culture in this country, and considerable

numbers of Mulgobas were soon propagated and planted along the lower

east coast of Florida. Recently, numerous other Indian varieties have

fruited in that state, some of them more valuable from a commercial

standpoint than Mulgoba, so that the latter probably will not retain

the prominent position which it has held. As regards California, the

exact date at which the mango was first introduced is not known, but it

is believed by F. Franceschi that it was first planted at Santa

Barbara, between 1880 and 1885.

1 History

of the West Indies, 1793.

|

|

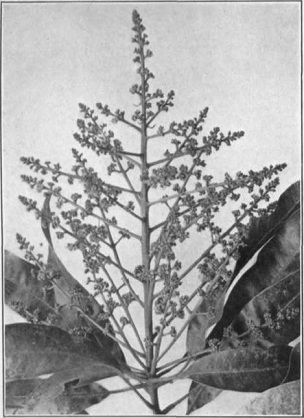

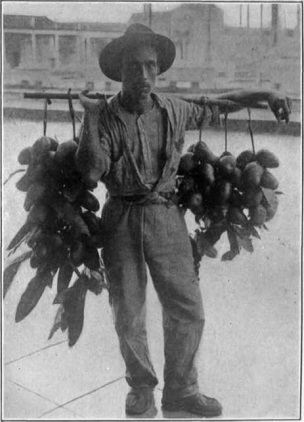

| Plate V. Left, inflorescence of the

Alphonse mango; right, a Cuban mango-vender. |

The

Mango

Botanical

Description

History and

Distribution

Composition

And Uses Of The Fruit

Climate

And Soil

Cultivation

Propagation

The Mango Flower

And Its Pollination

The

Crop

Pests And

Diseases

Races and

Varieties

Back to

The Mango Page

|

|