| Vanilla - Vanilla planifolia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

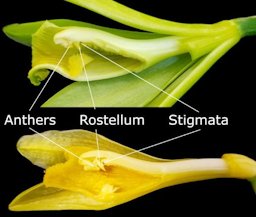

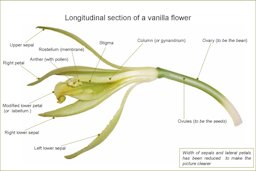

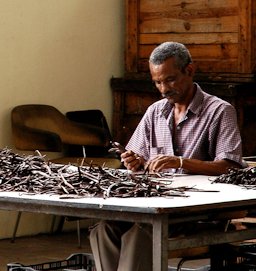

Fig. 1  Vanilla beans Vanilla planifolia  Fig. 2 V. planifolia at Garfield Park Conservatory  Fig. 3  Flat-leaved vanilla, Tahitian vanilla or West Indian vanilla, V. planifolia, Goa, India  Fig. 9   Fig. 10  V. planifolia flowering in Florida Southern College's greenhouses  Fig. 11  V. planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews  Fig. 12  Euglossa dilemma lured and captured at the UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education center. This bee could be a pollinator of vanilla orchids.  Fig. 13  V. planifolia (top) and V. pompona (bottom) flowers with anthers (pollinia), rostellum, and stigmata. The stigmata are shielded directly behind the rostellum.  Fig. 14  Longitudinal section of a vanilla flower  Fig. 21  V. planifolia, flower and seed pods forming  Fig. 22  V. planifolia at Garfield Park Conservatory (young seed pods)  Fig. 23  V. planifolia in Gothenburg Botanical Garden (immature and mature seed pods)  Fig. 24  V. fragrans, Bras-Panon, La Réunion Fig. 25  Gousses vertes de vanille (V. planifolia) au Jardin des parfums et des épices à l'île de La Réunion  Fig. 26  Gousses de vanillier presque mûres, Réunion (almost ripe seed pods)  Fig. 30  Culture. V. fragrans, Bras-Panon, La Réunion  Fig. 31  Kew Gardens. London  Fig. 32  A V. planifolia vine grown on Réunion Island (Maison de la Vanille, Saint-André) Fig. 33  Vanilla vines (V. planifolia) cultivated on Dracaena reflexa on Réunion island  Fig. 34 Fresh Vanilla fruit delivery in Bras-Panon, Réunion Island  Fig. 35  V. fragrans drying on clays, Bras-Panon, La Réunion  Fig. 36  Vanilla pods drying in Bras-Panon, Réunion Island.  Fig. 37  Trieur de vanille sur l'île de La Réunion Fig. 38  Vanilla: 6 beans  Fig. 39  Fig. 40  Panier de vanille à La Réunion  Fig. 41  Salon Marjolaine  Fig. 42  Vanilla extract  Fig. 43 Vanilla cream icing |

Scientific

name Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews Common names English: Bourdon vanilla, Madagascar-Bourbon vanilla, and Mexican vanilla (Lubinsky et al. 2008); French Polynesian: tumuvanira; French: vanille, goussedevanille (idiom), vanillier; German: vanille, vanilleschote (idiom); Italian: vaniglia, baccellodivaniglia (idiom); Japanese Rōmaji: banira; Portuguese: baunilha, favadabaunilha (idiom); Spanish: vainilla, mantecado, vainadelavainilla (idiom); Swedish: vanilj 7,15 Synonyms V. planifolia var. angusta Costantin & Boiss. ex C. Henry, V. planifolia var. gigantea Hoehne, V. planifolia var. macrantha Griseb, Epidendrum rubrum Lam., Myrobroma fragrans Salisb. nom. illeg., Notylia planifolia (Jacks. ex Andrews) Conz., N. sativa (Schiede) Conz., N. sylvestris (Schiede) Conz. nom. illeg., V. aromatica Willd. nom. illeg., V. bampsiana Geerinck, V. duckei Huber, V. fragrans Ames nom. illeg., V. rubra (Lam.) Urb., V. sativa Schiede, V. sylvestris Schiede, V. viridiflora Blume 6 Relatives V. abundiflora J.J. Smith., V. gardneri Rolfe., V. phaeantha H.G. Reichenb, V. pompona Schiede., V. tahitensis J.W. Moore 12 Family Orchidaceae (orchid family) Origin Mesoamerica USDA hardiness zones 10-12 10 Uses Food flavoring; cosmetics 1 Height Can reach 60 m (200 ft) in length 1 Spread 4-6 ft (1.2-1.8 m) Plant habit Fleshy, perennial vine with green stems; semi-epiphytic; monopodial climbing habit 1,4 Growth rate May grow 23.6-47 in. (60-120 cm) per month 12 Longevity Economic life of about 10-15 years 11 Trunk/bark/branches Stem diameter increases as the plant matures; produces aerial roots and terrestrial (ground) roots 1 Leaves Succulent; bright green; variable from 3–14 in. (8–35 cm) long; 0.75–3 in. (2–8 cm) wide; can survive 3-4 years on the vine 1 Flowers Large, flagrant; waxy cream; 2.5-3 in. (6-8 cm) long; 2 -4 in. (5-10 cm) in diameter; once a year; lasts 1 day 1 Blooms from April to July Fruit Pendulous narrowly cylindrical seed capsule (bean); 6-9 in. (15-23 cm) long; contains tiny, flavorless seeds 4,12 Season The vanilla pods are ready 9 months after pollination 3 Light requirement Shade, partial shade Soil tolerances Wide range of soil types; thrives in light soils with plenty of organic material; does not tolerate standing, stagnant, waterlogged or compacted soils 1,15 pH preference 5.5-7, tolerating 4.3-8 11 Drought tolerance Is drought tolerant Wind tolerance Not tolerant of wind Cold tolerance Optimum 69.8-86 °F (21-30 °C); tolerates 50-91.4 °F (10-33 °C) 11 Plant spacing 3–10 ft (1–3 m) apart; 8–10 ft (2.5–3 m) between rows 1 Roots Aerial roots and terrestrial roots; very susceptible to disturbance 1,3 Invasive potential * None reported Pest/disease resistance A major limitation to vanilla production in many regions is root and stem rot disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum 1 Known hazard Calcium oxalate crystals are present in the plant, which may cause dermatitis 9 Reading Materials Vanilla Growing in South Florida, University of Florida pdf Potential for Commercial Vanilla Production in Southern Florida, VSCNews Vanilla planifolia H.C. Andrews, PROSEA Foundation The Florida vanilla vine, ‘a big climbing orchid’, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden UF Scientists Sequence Vanilla Genome, Could Support Domestic Industry, UF/IFAS Blogs Origin V. planifolia spread from its native range in Mesoamerica across the Caribbean islands, into Europe, and then globally starting in the late 1500s. The development of manual pollination methods in 1837 and 1841 by Charles Morren and Edmund Albius, respectively, unlocked the potential of this species for commercial production outside Mesoamerica. 1 Distribution Globally from latitudes 27°N to 27°S. 1 Vanilla is indigenous to south-eastern Mexico, Guatemala and other parts of Central America and the Antilles. The important production areas are East Africa (Madagascar), the Comoro Islands, Reunion, Indonesia and French Oceania. In Indonesia vanilla is mainly cultivated on Java. 12 Description V. planifolia is a fleshy, perennial vine with green stems. The vines live for many years, and some species reach 60 m (200 ft) in length. The stem diameter increases as the plant matures. Vanilla is semi-epiphytic, meaning it is capable of rooting in the ground and also of growing on other plants without direct soil contact. 1 Vanilla extract is the second most valuable spice (after saffron) and is the world’s most popular flavor. Natural vanilla extract comes predominantly from the cured beans of V. planifolia, which is the major commercial species, and to a lesser extent from V. × tahitensis and V. pompona. 1

Types The three most common types of vanilla beans today are Bourbon or Bourbon-Madagascar vanilla beans, Mexican vanilla beans, and Tahitian vanilla beans 5 Bourbon vanilla, or Bourbon-Madagascar vanilla, produced from Vanilla planifolia plants introduced from the Americas, is the term used for vanilla from Indian Ocean islands such as Madagascar, the Comoros, and Réunion, formerly the Île Bourbon. They are the thinnest of the three types of beans and quite rich and sweet. 5 Mexican vanilla, made from the native Vanilla planifolia, is produced in much less quantity and marketed as the vanilla from the land of its origin. It is thick, with a smooth, rich flavor. 5 Tahitian vanilla is the name for vanilla from French Polynesia. It is the thickest and darkest of the three types, and intensely aromatic, but not as flavorful. 5 Leaves V. planifolia has succulent, bright green leaves. Mature leaves can be variable in size ranging from 8–35 cm (3–14 in) long and 2–8 cm (0.75–3 in) wide. They are lanceolate to oval-shaped with pointed tips and can survive about 3–4 years. Some types of V. planifolia have variegated leaves and are usually grown for ornamental purposes. 1

Flowers V. planifolia flowers are large and fragrant. Waxy cream-green sepals form on axillary inflorescences. V. pompona flowers are diagnostically yellow (Fig. 15) compared to V. planifolia (Fig. 16). Flowers can reach about 6 to 8 cm (2.5 to 3 in) in length and about 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 in) in diameter. Two of the petals are similar in appearance to the sepals. The third petal is modified into a lip shape. This lip-shaped petal contains two pollinia (pollen masses) and the stigma, mounted on a column. A structure situated between the stigma and pollinia, called the rostellum, effectively prevents auto-pollination. 1 The flowers typically appear during the drier times of year and are triggered by the lack of rainfall. They form in clusters of around 15 flowers, with only one flower opening each day. 3 They first appear 2–3 years after planting a new cutting. Vanilla tends to flower on larger vines when the diameter reaches 6–13 mm (0.25–0.5 in). Usually one but sometimes up to three flowers in a cluster can open at a time, usually early in the morning. Flowering usually occurs over a period of about 2 months, once a year, but each individual V. planifolia flower lasts for only one day. 1 If pollination does not occur the flower withers and drops in 1-2 days. The fruit reaches its maximum length about 6 weeks after fertilization, and ripens 7-9 months after flowering. 12

Fig. 15. V. pompona, West Indian vanilla, flower (note the difference in color with the V. planifolia flower) Fig. 16. V. planifolia Fig. 17. Note the unopened flowers in the background The V. pompona is a related species grown commercially on a limited scale in South America. 14 Fruit Following pollination, the ovary swells to produce a long seed capsule (bean) that can reach about 20 cm (8 in) in length and takes between 8–9 months to ripen. Vanilla beans contain thousands of tiny black, round seeds. At maturity, the bean will split open along two longitudinal seams, exposing the seeds and ruining the bean for commercial purposes. 1 Roots The root system is both epiphytic and terrestrial. The epiphytic or aerial roots are relatively long appresoria that anchor the vine on the tutor. They originate from the nodes in the stems and are seldom branched, light grey to tan with green to greenish-white tips formed by rapidly dividing and very active meristematic cells which can easily absorb water, and which owe their greenish colour to the chlorophyll they contain, which allows for a certain degree of photosynthesis in these tips. The central core of these roots is surrounded by the velamen, an extra layer of dead cells, which protects the vital tissues of the roots from drought, heat, and excessive sunlight, acting as a 'weather jacket'. 16 The same roots can grow down and bury themselves into the soil, then becoming terrestrial roots. But the most common terrestrial root systems growing into the soil originate from nodes in the stems that are buried in the soil. They are identical to the epiphytic roots, but they lose their green tips and grow horizontally to 30 or more feet (about 10 meters) from the crown in the upper 10 to 12 inches of soil (20 to 25 cm). They are generally much thicker than the aerial roots and are almost always branched. 16 Varieties V. planifolia has not generally benefited from modern plant breeding, so few named cultivars exist. Only a single cultivar, ‘Handa’, has been patented. This variety was developed by researchers from Réunion, and the future availability of this material is unknown. Otherwise, a few distinguishable types of V. planifolia have been characterized. These include ‘Mansa’ types originating from Mexico, which are commonly cultivated for commercial production. There are also two types of variegated V. planifolia generally available online and grown only for ornamental purposes. 1 V. × tahitensis is the second vanilla type grown on a commercial scale. Our current understanding is that V. × tahitensis is genetically mostly V. planifolia with a little V. odorata (another vanilla species) in its ancestry. V. pompona is commonly grown in southern Florida by hobbyists and is also commonly mistaken for V. planifolia. V. pompona is vigorous but reportedly produces a lower quality extract. 1 Cultural Requirements of the Vanilla Orchid [in pots], Art Buckman, Akatsuka Orchid Garden, Hawai'i pdf UF/IFAS Hopes to Grow Vanilla, Meet Consumer Demand, VSCNews Scientists Generating Recipe for Growing Vanilla in South Florida, VSCNews Pollination Auto-pollination of V. planifolia flowers is rare to nonexistent in regions where native pollinators (bees and perhaps hummingbirds) do not occur. Though not native, the orchid bee Euglossa dilemma (Fig. 12) has become established in southern Florida and could potentially be a pollinator of vanilla orchids. 1 V. planifolia is generally self-compatible, meaning that pollen from one flower can be used to fertilize the same flower and lead to seed and bean development. Pollination is reportedly low (~1%) in the native Mexican range even when pollinators are present. Thus, commercial vanilla production is heavily reliant on hand pollination. 1 To pollinate a vanilla flower, the rostellum that separates the pollinia and the stigma needs to be bypassed. Pollinations should be attempted in the morning, usually between 6 a.m. and noon. Hand pollination can be accomplished using a toothpick or other narrow implement. Sectioned V. planifolia and V. pompona flowers are shown in Fig. 19,20 to aid in describing pollination. The lower petal can be torn to expose the anthers with pollen (pollinia), rostellum, and stigmata. The rostellum is gently pushed up and away from the stigmata until the pollinia flap can be pushed towards the stigmata and make gentle contact with the stigmata. If the pollination is successful, the flower will be retained on the plant, otherwise it usually drops off in 2–3 days. Beans will rapidly begin to swell and elongate over a few weeks if successfully pollinated. 1 V. planifolia flowers must be pollinated the morning they open, before the flowers wither and drop off the vine.

Fig. 18. V. planifolia (vanilla) flower Fig. 19,20. Flower being hand pollinated. Pail o Waipio Huelo, Maui, Hawai'i

Propagation Vanilla is primarily propagated by cuttings. It is important to let cut sites heal prior to planting by leaving fresh cuttings at room temperature under low light for 1–2 days. All other factors being equal, the longer the cutting, the more quickly the vine will establish and begin to flower. Cuttings that are 30 cm (12 in.) long will generally require 3–4 years to flower, while meter-long cuttings should flower in 2–3 years. 1 Vanilla is not commonly propagated by seed due to germination challenges. The thick, highly lignified seed coat prevents timely germination, and seeds take significantly longer to grow into mature plants than cuttings. In addition, seed germination is likely reliant on associations with fungi or other microorganisms. Such constraints have supported the use of cuttings as the primary propagation method. 1 When propagating vanilla orchids from cuttings or harvesting ripe vanilla pods, care must be taken to avoid contact with the sap from the plant's stems. The sap of most species of Vanilla orchid which exudes from cut stems or where beans are harvested can cause moderate to severe dermatitis if it comes in contact with bare skin. 9 Planting New shoots of the vanilla cutting planted at the foot of a support tree are trained along its branches to encourage them to develop at a convenient height for pollination and harvesting. When shoots reach a length of about 2.5 m, they are carefully detached from the branch so that they may hang down. The tip (about 10 cm) of the vine is cut off 6-8 months before the flowering season, to encourage the production of inflorescences. New vegetative shoots on the apical part of the hanging vine are pruned, those on the basal part of the hanging vine are trained along the branches of the support tree. The latter will be the productive vines for the next season. 12 Trellising Vanilla vines require trellising to maximize production. Two major production methods are used. One uses “tutor” trees to provide both shade and a suitable structure on which the vines can climb. 1 More intensive cultivation under shade structures can increase yields. This system requires more initial investment for infrastructure but allows for increased planting density and yield potential. Trellis support systems vary greatly but are generally made of vertical wood or concrete supports with wire running between them. Supports vary in height but are usually no more than 2 m (6 ft) tall to facilitate pollination once vines mature. The post and wire system allows for greater control over vine spacing compared to tutor trees. Vines will need to be maintained on 15–20 cm (6–8 in) of a mulch substrate. 1 Pruning and Training Vines are trained to facilitate hand pollination and harvesting in a process called looping. Vines should be looped around supporting trellises or branches as they grow. Looping vines to the ground will stimulate terrestrial roots to form, especially if they are covered in mulch, leading to stronger vines. 1 Vanilla benefits greatly from a regular schedule to guide the vines. Once per week the plants should be checked for any vines that are trying to climb high, run along the ground or reaching for other plants. These vines need to be tucked back toward the living posts or draped around the branches of the post. The idea is to slowly create a figure eight with the vine, draping it back over itself. Vanilla plants won’t flower well if they only climb upwards and if they do, the flowers will be out of reach. 3 Looped, healthy vines from mature plants can be tipped (apex removed) to induce flowering. 1 Fertilizing Vanilla cultivation relies on the slow release of nutrients from decomposing organic material at the base of the support tree or post. 1 The best fertility program is ample mulching with leaves and woody branches and regular foliar sprays such as mountain microorganisms (using forest leaves), effective microorganisms, or actively aerated compost tea. The occasional application of high quality compost is encouraged. Avoid applying animal manure as the high nitrogen content encourages vegetative growth over flowering. 3 Irrigation Vanilla requires about two months of a dry season to initiate flowering. Excessively wet conditions during capsule ripening can lead to bean rot. Supplemental irrigation can be useful for establishing new cuttings and potentially for frost protection. 1 Harvesting and Curing Beans begin to yellow at the blossom end when fully mature. Care should be taken not to harvest beans prematurely, because this negatively impacts the quality of the resulting extract. V. planifolia beans that are left on the vine for too long have a higher propensity to split or mold, eliminating their economic value. The exception to this is V. × tahitensis, which does not display the bean-splitting trait and can be left on the vine until completely brown. Individual beans should be carefully removed from the raceme in order to avoid damaging the beans. 1 Vanilla beans must be cured in order to develop the characteristic vanilla aroma and flavor. Curing outcomes vary greatly by location and are heavily influenced by the growing environment, plant genetics, and maturity of the beans. Curing vanilla beans remains somewhat of an art, with many variations being used in different parts of the world. In general, curing includes a few major steps: sorting, heat-killing, sweating, gradual drying, and conditioning. 1 Freshly harvested green fruits contain about 80% water which is reduced to about 20% by curing and drying. 12 After harvest, the fresh vanilla pods have no aroma, but must be cured for four to five months—a process of drying and fermenting pods, which encourages secretion of vanillin in tiny crystals on the outside of the pod. 15

Fig. 27. Beans must be picked at the proper time in order to secure the highest aroma and quality during curing. The bean on the left is too green; the second and third beans to the right are of proper maturity, with the tips beginning to turn yellow; the fourth and fifth beans on the right are over- mature, both showing splitting, and the one on the right beginning to turn black. The latter two beans will be sold as ''cuts'' at reduced profit. Vanilla Production.... in Florida? UF/IFAS Blogs Vanilla, Post-harvest Operations, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations pdf

Fig. 28. Vanille Bourbon de Madagascar, David Vanille Fig. 29. Vanilla products USA 10 Madagascar Bourbon Planifolia Extract Grade B vanilla beans 4-5 in. (12-14 cm ) Pests Insect pests generally do not typically cause serious damage. Snails and slugs, however, can be problematic if not controlled. We have noticed larval feeding on young plants, but we were able to manually remove the pests. 1 Diseases A major limitation to vanilla production in many regions is root and stem rot disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Fusarium is a ubiquitous soilborne fungus that causes rot in many species. One specialized type (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radices-vanillae) causes rot in vanilla in all major producing areas by penetrating roots and spreading throughout the plant. 1 Three main commercial preparations of natural vanilla: Whole pod. Powder (ground pods, kept pure or blended with sugar, starch or other ingredients) The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 12.5 percent of pure vanilla (ground pods or oleoresin) in the mixture (FDA 1993). 4 Extract (in alcoholic solution). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 35 percent vol. of alcohol and 13.35 ounces of pod per gallon. 5 Storage The pods can be stored, several years, in an airtight jar with an alcohol base (rum, gin, vodka). Only one end of your pod should be in contact with the alcohol bottom. You can also freeze your pods for 24 months. 13 Food Uses The cured fruit pods are used to flavour food. Vanilla flavoring in food may be achieved by adding vanilla extract or by cooking vanilla pods in the liquid preparation. A stronger aroma may be attained if the pods are split in two, exposing more of the pod's surface area to the liquid. In this case, the pods' seeds are mixed into the preparation. Natural vanilla gives a brown or yellow color to preparations, depending on the concentration. 4 A product labeled "natural vanilla flavor" contains only pure vanilla extract, while one labeled "vanilla flavoring" involves both pure and imitation vanilla. Although pure vanilla extract is more expensive, it is generally preferred in terms of flavor intensity and quality, and with less needed, while imitation vanilla is considered to have a harsh quality with a bitter aftertaste. 5 A major use of vanilla is in flavoring ice cream.

Fig. 44. Vanilla infused sugar Fig. 45. Vanilla ice cream Fig. 46. Vanilla flan Fig. 47. Japanese delicacy, the delicious vanilla-matcha soft serve, Higashiyama, Kyoto Fig. 48. Ice cream with praline sauce Fig. 49. A beer float made with Breyers vanilla ice cream and Samuel Adams beer Nutrient Content 5 g, fat 11 g, sugar 7-9 g, fiber 15-20 g, ash 5-10 g, vanillin 1.5-3 g, a soft resin 2 g and an odourless vanillic acid. The vanillin content of cured Indonesian vanilla is high (2.75%) in comparison with cured vanilla from other sources: Mexico 1.75%, Sri Lanka 1.5%, Tahiti 1.7%. Vanilla fruits from Tahiti contain heliotropin which gives them their distinctive flavour. 12 Chemical composition of processed vanilla beans

Medicinal Properties ** In traditional medicine vanilla fruits are used as an aphrodisiac, carminative, emmenagogue and stimulant; they are said to reduce or cure fevers, spasms and caries. Vanilla extracts (especially tinctures according to pharmacopoeias) are used in pharmaceutical preparations such as syrups, primarily as a flavouring agent. 12 Other Uses Vanilla is one of the most recommended products for: • Sweetness potentiator • Bitterness maskant • Reduces burning, biting sensations • Essential oils of vanilla and vanillin are used in aromatherapy: pain reduction in women; calming, reduces the startle reflex • Fragrance: Perfume, candles, air fresheners, incense, household, • Baby, and personal care products • Medicinal: psychological, Sloane-Kettering reported 63% reduction in stress level of MRI patients; reported cure of sexual dysfunction in men • Insect Repellant • Odor Maskant: paint, industrial chemicals, rubber tires, plastics 2 General Florida has four native vanilla species (V. barbellata, V. dilloniana, V. phaeantha, and V. mexicana) with naturalized V. planifolia (Fig. 52) .The native Florida vanilla species are endangered and should not be collected from natural areas without proper authorization and permitting by regulatory authorities. 1 The vanilla orchid (Vanilla planifolia) is one of the world’s most interesting plants. Of the nearly 35,000 species of orchid, the second largest botanical family of plants, vanilla is the only species that produces an edible fruit. 3 Vanilla powder is produced by grinding the whole, dried bean, while vanilla extract is made by macerating chopped beans in a solution to extract the flavor and then aging the mixture. 5 Genus name comes from the Spanish name vainilla meaning a small pod with reference to the shape of the fruit. In major consuming countries (United States, European Union) vanilla is the only spice which benefits from a 'Standard of Identity' which helps shield vanilla beans from competition from substitutes. 12

Fig. 50. Flowers of V. planifolia (top left), V. pompona (top center), V. phaeantha (top right), V. mexicana (bottom left), V. dilloniana (bottom center), and V. barbellata (bottom right) growing in southern Florida. Fig. 51. Stamp of Guadeloupe (French colony); 1905. Postes, télégraphes et téléphones (PTT) of the Troisième République Française. Drawing with the harbour of Basse-Terre (capital of Guadeloupe) with the volcano "La Soufriere" in background and vanilla vines and vanilla beans (of the plant "Category: Vanilla planifolia") as frame decoration.  Fig. 52  Fig. 52. Vanilla distribution map, wild populations Further Reading Vanilla, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Vanilla, Sub-Tropical Fruit Club of Qld Vanilla, University of Wisconsin – Madison pdf Vanilla Cultivation: A Practical Guide for the Tropical Homestead, Porvenir Design ext. link Vanilla Growing in Uganda, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Vanilla planifolia: history, botany and culture in Reunion island, Hal archives-ouvertes pdf Vanilla Botanical Art Older Material Vanilla Culture in Hawai'i, 1903, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture pdf Vanilla: a promising new crop for Porto Rico, 1919, Porto Rico Agricultural Experiment Station pdf Vanilla Culture in Puerto Rico, 1948, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture pdf List of Growers and Vendors |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 Chambers, Alan, et al. "Vanilla Growing in South Florida." Horticultural Sciences Dept, UF/IFAS Extension, HS1348, Original pub. Nov. 2019, Revised Jan. 2023, and Feb. 2024, AskIFAS, doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1348-2024,(CC BY-NC-ND-4.0), edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1348. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019, 9Jan. 2024, 12 Apr. 2024. 2 De La Cruz Medina, Javier, et al. "VANILLA: Post-harvest Operations." Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 16 June 2009, FAO, www.fao.org/3/a-ax447e.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec. 2019. 3 Gallant, Scott and Laura Killingbeck. "Vanilla Cultivation: A Practical Guide for the Tropical Homestead." 5 Dec. 2018, Porvenir Design, www.porvenirdesign.com/blog/2018/11/27/vanilla-cultivation-a-practical-guide-for-the-tropical-homestead. Accessed 14 Dec. 2019. 4 "Vanilla." New World Encyclopedia, www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Vanilla. Accessed 14 Dec. 2019. 5 Herbst, Sharon Tyler. The New Food Lover's Companion: Comprehensive Definitions of Nearly 6,000 Food, Drink, and Culinary Terms. Barron's Cooking Guide. 3rd Edition, New York, Barron's Educational Series, 2001. 6 "Synonyms for Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews." The Plant List (2013), Version 1.1, USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database, www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/search?q=vanilla+planifolia. Accessed 15 Dec. 2019. 7 "Taxon: Vanilla planifolia Andrews." USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System, Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN-Taxonomy), National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, 2019, U.S. National Plant Germplasm System, npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?id=41111. Accessed 15 Dec. 2019. 9 "Vanilla." Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#Contact_dermatitis. Accessed 17 Dec. 2019. 10 "Vanilla planifolia - Jacks. ex Andrews." Plants For A Future, pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Vanilla+planifolia. Accessed 17 Dec. 2019. 11 "Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews." Ecocrop, ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/home, Plants For A Future, pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Vanilla+planifolia. Accessed 17 Dec. 2019. 12 Straver, J. T. G. "Vanilla planifolia H.C. Andrews." Spices, Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 13, Edited by Guzman, C. C. and Siemonsma, J. S., PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia, Record no. 602, 1999, PROSEA Foundation, www.prota4u.org/prosea/view.aspx?id=602. Accessed 17 Dec. 2019. 13 Vanille, David. "Bourbon vanilla beans." David Vanille, www.davidvanille.com/en/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. 14 Chambers, Alan. "Scientists Developing Recipe for Growing Vanilla in South Florida." Vegetable and Specialty Crop News, 17 Dec. 2019, vscnews.com/scientists-developing-recipe-growing-vanilla-south-florida/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. 15 Uchida, Janice Y. "Farm and Forestry Production and Marketing Profile for Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia)." Specialty Crops for Pacific Island Agroforestry, agroforestry.org/images/pdfs/Vanilla_specialty_crop.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec. 2019 16 "Vanilla." Fruit Gardener, California Rare Fruit Growers, Nov. 1988, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia, July 1989, rfcarchives.org.au//Next/Fruits/Vanilla/Vanilla7-89.htm. Accessed 24 Dec. 2019. Videos V1 Diaper, David. "Vanilla facts from the Eden Project's Rainforest Biome." Eden Project, www.edenproject.com/learn/for-everyone/plant-profiles/vanilla. Accessed 27 Dec. 2019. V2 Green, William. "Pollinating a Vanilla flower." My Green Pets, YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RdoTcDD2EU. Accessed 27 Dec. 2019. Photographs Fig. 1 Fou, Augustine. "Vanilla beans." Flickr, 11 Jan. 2009, (CC BY 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/acfou/3189690364/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023. Fig. 2 Ziarnek, Krzysztof. "Vanilla planifolia at Garfield Park Conservatory." Encyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 53185375, 2 Sept. 2016, EOL, (CC BY-SA-3.0), eol.org/media/7985961. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 3 Garg, J. M . "Flat-leaved Vanilla, Tahitian Vanilla or West Indian Vanilla, Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews, Goa, India." Wikimedia Commons, 30 Sept. 2009, (CC BY 3.0), GNU 1.2, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_planifolia_W_IMG_2452.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 4 Ziarnek, Krzysztof. "Vanilla planifolia at Garfield Park Conservatory." Encyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 53185580, 2 Sept. 2016, EOL, (CC BY-SA-3.0), eol.org/media/7985965. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 5,6,7Janzen, Daniel H. "Stem." Guanacaste Dry Forest Conservation Fund, 2010, EOL, (CC BY-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/1127948/media. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 8 Escudero, Juan Carlos Olivo. "Vainilla, Vanilla planifolia Andrews. Veracruz, Mexico." iNaturalist, 8658077, 25 July 2017, GBIF, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.gbif.org/occurrence/1571182651. Accessed 22 Dec. 2019. Fig. 9 Osen, James. "Vanilla planifolia." Smithsonian Gardens Orchid Collection, Accession no. 2007-0282A, 29938661, EOL, (CC BY-SA-3.0), eol.orgmedia/9462801. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 10 Manners, Malcolm. "Vanilla planifolia flowering in Florida Southern College's greenhouses." Wikimedia Commons, via Flickr, 11 Mar. 2012, (CC BY 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vanilla_planifolia_(6998639597).jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 11 "Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews." National Museum of Natural History, Botany Dept., NMNH, www.si.edu/object/nmnhbotany_10279376. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 12 Carillo, Daniel. "Euglossa dilemma lured and captured at the UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education center." Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, IFAS Extension, HS1348, Original pub. Nov. 2019, EDIS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1348. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019. Fig. 13 Chambers, Alan. "V. planifolia (top) and V. pompona (bottom) flowers with anthers (pollinia), rostellum, and stigmata." Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, IFAS Extension, HS1348, Original pub. Nov. 2019, EDIS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1348. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019. Fig. 14 navez. B. "Longitudinal section of a vanilla flower." 11 Jan. 2006, Wikipedia, (CC BY-SA 3.0), GNU I.2, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:VanillaFlowerLongitudinalSection-en.png. Accessed 15 Dec. 2019. Fig. 15 Popovkin, Alex. "Vanilla pompona Schiede." Encyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 30440568661, 20 Oct. 2016, EOL, (CC BY), eol.orgmedia/6648479. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 16 Alberto Soto, Jose. "Vanilla planifolia, Venezuela." Encyclopedia of Life, via iNaturalist, 4109816, 6 Mar. 2015, EOL, (CC BY-NC), eol.org/media/4652287. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 17 Hammer, Roger. "Vanilla planifolia." Wildflowers of the Everglades, Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2019, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/photo.aspx?ID=7508. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 18 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Vanilla planifolia (Vanilla). Flower. Pali o Waipio Huelo, Maui, Hawai'i." 27 May 2019, no. 190527-6594, Starr Environmental, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=48301554672. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 19 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Vanilla planifolia (Vanilla). Flower being hand polinated. Pali o Waipio Huelo, Maui, Hawai'i." 12 Mar. 2013, no. 130312-2168, Starr Environmental, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=25180555486. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 20 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Vanilla planifolia (Vanilla). Flower being hand polinated. Pali o Waipio Huelo, Maui, Hawai'i." 12 Mar. 2013, no. 130312-2171, Starr Environmental, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=25113649041. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 21 Dennis-Mada. "Vanilla planifolia." iNaturalist, 5664314, EOL, (CC BY-NC 4.0), eol.org/pages/47387914/media. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 22 Ziarnek, Krzysztof. "Vanilla planifolia at Garfield Park Conservatory." Encyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 55318578, 2 Sept. 2016, EOL, (CC BY-SA-3.0), eol.org/media/7985964. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 23 Averater. "Vanilla planifolia in Gothenburg Botanical Garden." Wikimedia Commons, 30 June 2015, (CC BY 3.0), GNU 1.2, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vanilla_planifolia_GotBot_2015_001.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 24 Bouba. "Vanilla fragrans, Bras-Panon, La Réunion." Wikimedia Commons, Nov. 2004, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vanilla_fragrans_2.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 25 navez, B. "Gousses vertes de vanille (Vanilla planifolia) au Jardin des parfums et des épices à l'île de La Réunion." Wikimedia Commons, 6 June 2009, (CC BY-SA 3.0), (CC BY-SA 2.0), (CC BY-SA 1.0), GNU 1.2, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vanilla_planifolia_cluster_of_green_pods.JPG. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 26 Fpalli. "Gousses de vanillier presque mûres, Réunion." Wikimedia Commons, 12 July 2004, (CC BY SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_planifolia_(Vanille).jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 27 "Vanilla culture in Puerto Rico." Internet Archive Book Images, Plate 1, p. 56, U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library, 1948, Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/20576400351/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 28 Alphaomega1010. "Bourbon vanilla beans." David Vanille, 24 Sept. 2012, Wikimedia Commons, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanille_Bourbon#/media/File:Bourbon_vanilla_beans_-_extra_noire_-_+20cm.JPG. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 29 Weaver, Wendy. "Vanilla Products USA 10 Madagascar Bourbon Planifolia Extract Grade B Vanilla Beans 12~14 cm (4~5 inches)." Flickr, 22 Nov. 2019, Public Domain, www.flickr.com/photos/185621511@N03/49105334086/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 30 Bouba. "Culture. Vanilla fragrans, Bras-Panon, La Réunion." Wikimedia Commons, Nov. 2004, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vanilla_fragrans_3.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 31 User: Mmparedes. "Kew Gardens. London." Wikimedia Commons, 3 Apr. 2007, (CC BY-SA 2.5), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_planifolia3.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 32 Monniaux, David. " A Vanilla planifolia vine grown on Réunion Island (Maison de la Vanille, Saint-André)." Wikimedia Commons, 31 Dec. 2004, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_plantation_dsc01187.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 33 navez, B. "Vanilla vines (Vanilla planifolia) cultivated on Dracaena reflexa on Réunion island." Wikimedia Commons, 12 Dec. 2006, (CC BY-SA 3.0), GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_on_Dracaena.JPG. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 34 Canli, Ekrem. "Vanilla pods drying in Bras-Panon, Réunion Island." Wikimedia Commons, 12 July 2015, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanille_Bourbon#/media/File:Vanilla_fruit_réunion5.jpg. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 35 Bouba. "Vanilla fragrans drying on trays, Bras-Panon, La Réunion," Wikimedia Commons, 11 Dec. 2004, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_fragrans_4.jpg. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 36 Canli, Ekrem. "Vanilla pods drying in Bras-Panon, Réunion Island." Wikimedia Commons, 12 July 2015, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanille_Bourbon#/media/File:Vanilla_fruit_réunion4.jpg. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 37 Tirados, Joselito. "Trieur de vanille sur l'île de La Réunion." Wikimedia Commons, via Flickr, 26 Oct. 2004, (CC BY 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanille_Bourbon#/media/File:Trieur_de_vanille_-_La_Réunion.jpg. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 38 navez, B. "Vanilla: 6 beans," Wikimedia Commons, 26 Nov. 2005, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:Vanilla_6beans.JPG. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019. Fig. 39 Fou, Augustine. "Vanilla." Flickr, 1 Apr. 2008, (CC BY 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/acfou/3188847157/in/photostream/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023. Fig. 40 Tirados, Joselito. "Panier de vanille à La Réunion." Wikimedia Commons, via Flickr, 26 Oct. 2004, (CC BY 2.0), Image cropped, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanille_Bourbon#/media/File:Vanille_-_La_Réunion.jpg. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 41 Georges, J. J. "Salon Marjolaine." Wikimedia Commons, 9 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), Imaged cropped, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanille_Bourbon#/media/File:Salon_Marjolaine_2018_49.jpg. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 42 Boucheron, Brian. "Vanilla Extract." Flickr, Aug. 19, 2012, (CC BY 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/bert_m_b/7820058554/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 43 "Dessert Food Cream." Pik Wizard, (CC0), pikwizard.com/photos/81b00facb059257a42f7d2357bc40092-l.jpg. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 44 gate74. Pixabay, Public Domain, pixabay.com/photos/vanilla-pod-sugar-bowl-food-sweet-2519484/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 45 ponce_photography. Pixabay, Public Domain, pixabay.com/photos/ice-cream-fruit-raspberry-summer-1440834/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 46 RitaE. Pixabay, Public Domain, pixabay.com/photos/caramel-cream-flan-milk-egg-sugar-1958358/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 47 Sopakuwa, Gilbert. "Japanese delicacy, the delicious vanilla-matcha soft serve. Higashiyama, Kyoto." 9 Nov. 2019, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), Image cropped, www.flickr.com/photos/g-rtm/49091368986/. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 48 Luisfi. "Ice cream with praline sauce." Wikimedia Commons, 28 Mar. 2014, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:140329_helado_vainilla_praline_cointreau-luis_figueroa-luisfi61.JPG. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 49 Danforth, Nicholas. "A beer float made with Breyers vanilla ice cream and Samuel Adams beer." Wikimedia Commons, via Flickr, 18 May 2008, (CC BY 2.0), Image cropped, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beer_float.jpg. Accessed 23 Dec. 2019. Fig. 50 Chambers, Alan. "Flowers of V. planifolia (top left), V. pompona (top center), V. phaeantha (top right), V. mexicana (bottom left), V. dilloniana (bottom center), and V. barbellata (bottom right) growing in southern Florida." Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, IFAS Extension, HS1348, Original pub. Nov. 2019, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1348. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019. Fig. 51 User: Katharinaiv. "Stamp of Guadeloupe (French colony); 1905." Postes, télégraphes et téléphones (PTT) of the Troisième République Française, 31 Dec. 1904, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vanilla_planifolia#/media/File:GLP_1905_MiNr0052_mt_B002.jpg. Accessed 18 Dec. 2019. Fig. 52 "Species Distribution Map." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2019, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=4008. Accessed 15 Dec. 2019. * UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas ** Information provided is not intended to be used as a guide for treatment of medical conditions. Published 28 Dec. 2019 LR. Last update 24 Dec. 2024 LR |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||